Parsing expression grammar

In computer science, a parsing expression grammar, or PEG, is a type of analytic formal grammar, i.e. it describes a formal language in terms of a set of rules for recognizing strings in the language. The formalism was introduced by Bryan Ford in 2004[1] and is closely related to the family of top-down parsing languages introduced in the early 1970s. Syntactically, PEGs also look similar to context-free grammars (CFGs), but they have a different interpretation: the rules of PEGs are ordered. This is closer to how string recognition tends to be done in practice, e.g. by a recursive descent parser.

Unlike CFGs, PEGs cannot be ambiguous; if a string parses, it has exactly one valid parse tree. This makes PEGs well-suited to parsing computer languages, but not natural languages.

Contents |

Definition

Syntax

Formally, a parsing expression grammar consists of:

- A finite set N of nonterminal symbols.

- A finite set Σ of terminal symbols that is disjoint from N.

- A finite set P of parsing rules.

- An expression eS termed the starting expression.

Each parsing rule in P has the form A ← e, where A is a nonterminal symbol and e is a parsing expression. A parsing expression is a hierarchical expression similar to a regular expression, which is constructed in the following fashion:

- An atomic parsing expression consists of:

- any terminal symbol,

- any nonterminal symbol, or

- the empty string ε.

- Given any existing parsing expressions e, e1, and e2, a new parsing expression can be constructed using the following operators:

- Sequence: e1 e2

- Ordered choice: e1 / e2

- Zero-or-more: e*

- One-or-more: e+

- Optional: e?

- And-predicate: &e

- Not-predicate: !e

Semantics

The fundamental difference between context-free grammars and parsing expression grammars is that the PEG's choice operator is ordered. If the first alternative succeeds, the second alternative is ignored. Thus ordered choice is not commutative, unlike unordered choice as in context-free grammars and regular expressions. Ordered choice is analogous to soft cut operators available in some logic programming languages.

The consequence is that if a CFG is transliterated directly to a PEG, any ambiguity in the former is resolved by deterministically picking one parse tree from the possible parses. By carefully choosing the order in which the grammar alternatives are specified, a programmer has a great deal of control over which parse tree is selected.

Like boolean context-free grammars, parsing expression grammars also add the and- and not- predicates. These facilitate further disambiguation, if reordering the alternatives cannot specify the exact parse tree desired.

Operational interpretation of parsing expressions

Each nonterminal in a parsing expression grammar essentially represents a parsing function in a recursive descent parser, and the corresponding parsing expression represents the "code" comprising the function. Each parsing function conceptually takes an input string as its argument, and yields one of the following results:

- success, in which the function may optionally move forward or consume one or more characters of the input string supplied to it, or

- failure, in which case no input is consumed.

A nonterminal may succeed without actually consuming any input, and this is considered an outcome distinct from failure.

An atomic parsing expression consisting of a single terminal succeeds if the first character of the input string matches that terminal, and in that case consumes the input character; otherwise the expression yields a failure result. An atomic parsing expression consisting of the empty string always trivially succeeds without consuming any input. An atomic parsing expression consisting of a nonterminal A represents a recursive call to the nonterminal-function A.

The sequence operator e1 e2 first invokes e1, and if e1 succeeds, subsequently invokes e2 on the remainder of the input string left unconsumed by e1, and returns the result. If either e1 or e2 fails, then the sequence expression e1 e2 fails.

The choice operator e1 / e2 first invokes e1, and if e1 succeeds, returns its result immediately. Otherwise, if e1 fails, then the choice operator backtracks to the original input position at which it invoked e1, but then calls e2 instead, returning e2's result.

The zero-or-more, one-or-more, and optional operators consume zero or more, one or more, or zero or one consecutive repetitions of their sub-expression e, respectively. Unlike in context-free grammars and regular expressions, however, these operators always behave greedily, consuming as much input as possible and never backtracking. (Regular expression matchers may start by matching greedily, but will then backtrack and try shorter matches if they fail to match.) For example, the expression a* will always consume as many a's as are consecutively available in the input string, and the expression (a* a) will always fail because the first part (a*) will never leave any a's for the second part to match.

Finally, the and-predicate and not-predicate operators implement syntactic predicates. The expression &e invokes the sub-expression e, and then succeeds if e succeeds and fails if e fails, but in either case never consumes any input. Conversely, the expression !e succeeds if e fails and fails if e succeeds, again consuming no input in either case. Because these can use an arbitrarily complex sub-expression e to "look ahead" into the input string without actually consuming it, they provide a powerful syntactic lookahead and disambiguation facility.

Examples

This is a PEG that recognizes mathematical formulas that apply the basic four operations to non-negative integers.

Value ← [0-9]+ / '(' Expr ')'

Product ← Value (('*' / '/') Value)*

Sum ← Product (('+' / '-') Product)*

Expr ← Sum

In the above example, the terminal symbols are characters of text, represented by characters in single quotes, such as '(' and ')'. The range [0-9] is also a shortcut for ten characters, indicating any one of the digits 0 through 9. (This range syntax is the same as the syntax used by regular expressions.) The nonterminal symbols are the ones that expand to other rules: Value, Product, Sum, and Expr.

The examples below drop quotation marks in order to be easier to read. Lowercase letters are terminal symbols, while capital letters in italics are nonterminals. Actual PEG parsers would require the lowercase letters to be in quotes.

The parsing expression (a/b)* matches and consumes an arbitrary-length sequence of a's and b's. The rule S ← a S? b describes the simple context-free "matching language"  . The following parsing expression grammar describes the classic non-context-free language

. The following parsing expression grammar describes the classic non-context-free language  :

:

S ← &(A c) a+ B !(a/b/c) A ← a A? b B ← b B? c

The following recursive rule matches standard C-style if/then/else statements in such a way that the optional "else" clause always binds to the innermost "if", because of the implicit prioritization of the '/' operator. (In a context-free grammar, this construct yields the classic dangling else ambiguity.)

S ← if C then S else S / if C then S

The parsing expression foo &(bar) matches and consumes the text "foo" but only if it is followed by the text "bar". The parsing expression foo !(bar) matches the text "foo" but only if it is not followed by the text "bar". The expression !(a+ b) a matches a single "a" but only if it is not the first in an arbitrarily-long sequence of a's followed by a b.

The following recursive rule matches Pascal-style nested comment syntax, (* which can (* nest *) like this *). The comment symbols appear in double quotes to distinguish them from PEG operators.

Begin ← "(*" End ← "*)" C ← Begin N* End N ← C / (!Begin !End Z) Z ← any single character

Implementing parsers from parsing expression grammars

Any parsing expression grammar can be converted directly into a recursive descent parser.[2] Due to the unlimited lookahead capability that the grammar formalism provides, however, the resulting parser could exhibit exponential time performance in the worst case.

It is possible to obtain better performance for any parsing expression grammar by converting its recursive descent parser into a packrat parser, which always runs in linear time, at the cost of substantially greater storage space requirements. A packrat parser[2] is a form of parser similar to a recursive descent parser in construction, except that during the parsing process it memoizes the intermediate results of all invocations of the mutually recursive parsing functions, ensuring that each parsing function is only invoked at most once at a given input position. Because of this memoization, a packrat parser has the ability to parse many context-free grammars and any parsing expression grammar (including some that do not represent context-free languages) in linear time. Examples of memoized recursive descent parsers are known from at least as early as 1993.[3] Note that this analysis of the performance of a packrat parser assumes that enough memory is available to hold all of the memoized results; in practice, if there were not enough memory, some parsing functions might have to be invoked more than once at the same input position, and consequently the parser could take more than linear time.

It is also possible to build LL parsers and LR parsers from parsing expression grammars, with better worst-case performance than a recursive descent parser, but the unlimited lookahead capability of the grammar formalism is then lost. Therefore, not all languages that can be expressed using parsing expression grammars can be parsed by LL or LR parsers.

Advantages

Compared to pure regular expressions (i.e. without back-references), PEGs are strictly more powerful, but require significantly more memory. For example, a regular expression inherently cannot find an arbitrary number of matched pairs of parentheses, because it is not recursive, but a PEG can. However, a PEG will require an amount of memory proportional to the length of the input, while a regular expression matcher will require only a constant amount of memory.

Any PEG can be parsed in linear time by using a packrat parser, as described above.

Parsers for languages expressed as a CFG, such as LR parsers, require a separate tokenization step to be done first, which breaks up the input based on the location of spaces, punctuation, etc. The tokenization is necessary because of the way these parsers use lookahead to parse CFGs that meet certain requirements in linear time. PEGs do not require tokenization to be a separate step, and tokenization rules can be written in the same way as any other grammar rule.

Many CFGs contain ambiguities, even when they're intended to describe unambiguous languages. The "dangling else" problem in C, C++, and Java is one example. These problems are often resolved by applying a rule outside of the grammar. In a PEG, these ambiguities never arise, because of prioritization.

Disadvantages

Memory consumption

PEG parsing is typically carried out via packrat parsing, which uses memoization[4][5] to eliminate redundant parsing steps. Packrat parsing requires storage proportional to the total input size, rather than the depth of the parse tree as with LR parsers. This is a significant difference in many domains: for example, hand-written source code has an effectively constant expression nesting depth independent of the length of the program—expressions nested beyond a certain depth tend to get refactored.

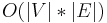

For some grammars and some inputs, the depth of the parse tree can be proportional to the input size, [6] so both an LR Parser and a packrat parser will appear to have the same worst-case asymptotic performance. A more accurate analysis would take the depth of the parse tree into account separately from the input size. This is similar to a situation which arises in graph algorithms: the Bellman–Ford algorithm and Floyd–Warshall algorithm appear to have the same running time ( ) if only the number of vertices is considered. However, a more accurate analysis which accounts for the number of edges as a separate parameter assigns the Bellman–Ford algorithm a time of

) if only the number of vertices is considered. However, a more accurate analysis which accounts for the number of edges as a separate parameter assigns the Bellman–Ford algorithm a time of  , which is only quadratic in the size of the input (rather than cubic).

, which is only quadratic in the size of the input (rather than cubic).

Indirect left recursion

PEGs cannot express left-recursive rules where a rule refers to itself without moving forward in the string. For example, in the arithmetic grammar above, it would be tempting to move some rules around so that the precedence order of products and sums could be expressed in one line:

Value ← [0-9.]+ / '(' Expr ')'

Product ← Expr (('*' / '/') Expr)*

Sum ← Expr (('+' / '-') Expr)*

Expr ← Product / Sum / Value

In this new grammar matching an Expr requires testing if a Product matches while matching a Product requires testing if an Expr matches. This circular definition cannot be resolved. However, left-recursive rules can always be rewritten to eliminate left-recursion. For example, the following left-recursive CFG rule:

string-of-a ← string-of-a 'a' | 'a'

can be rewritten in a PEG using the plus operator:

string-of-a ← 'a'+

The process of rewriting indirectly left-recursive rules is complex in some packrat parsers, especially when semantic actions are involved.

With some modification, traditional packrat parsing can support direct left recursion.[2][7] ,[8] but doing so results in a loss of the linear-time parsing property[7] which is generally the justification for using PEGs and Packrat Parsing in the first place. Only the OMeta parsing algorithm[9] supports full direct and indirect left recursion without additional attendant complexity (but again, at a loss of the linear time complexity), whereas all GLR parsers support left recursion.

Subtle grammatical errors

In order to express a grammar as a PEG, the grammar author must convert all instances of nondeterministic choice into prioritized choice. Unfortunately, this process is error prone, and often results in grammars which mis-parse certain inputs. An example and commentary can be found here.

Expressive power

Packrat parsers cannot recognize some unambiguous grammars, such as the following (example taken from[10])

S ← 'x' S 'x' | 'x'

In fact, neither LL(k) nor LR(k) parsing algorithms are capable of recognizing this example.

Maturity

PEGs are new and not widely implemented. By contrast, regular expressions and CFGs have been around for decades, the code to parse them has been extensively optimized, and many programmers are familiar with how to use them. This is not all that compelling an objection to the adoption and use of PEGs, of course, since there was a time when the same considerations applied to the older approaches as well.

See also

- Formal grammar

- Regular expressions

- Top-down parsing language

- Comparison of parser generators

- Parser combinators

References

- ^ Ford, Bryan p (2004). "Parsing Expression Grammars: A Recognition Based Syntactic Foundation". Proceedings of the 31st ACM SIGPLAN-SIGACT Symposium on Principles of Programming Languages. ACM. doi:10.1145/964001.964011. ISBN 1-58113-729-X. http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=964001.964011. Retrieved 2010-07-30.

- ^ a b c Ford, Bryan (September 2002). "Packrat Parsing: a Practical Linear-Time Algorithm with Backtracking". Massachusetts Institute of Technology. http://pdos.csail.mit.edu/~baford/packrat/thesis. Retrieved 2007-07-27.

- ^ Merritt, Doug (November 1993). "Transparent Recursive Descent". Usenet group comp.compilers. http://compilers.iecc.com/comparch/article/93-11-012. Retrieved 2009-09-04.

- ^ Bryan Ford. "The Packrat Parsing and Parsing Expression Grammars Page". http://pdos.csail.mit.edu/~baford/packrat/. Retrieved 23 Nov 2010.

- ^ Rick Jelliffe. "What is a Packrat Parser? What are Brzozowski Derivatives?". http://broadcast.oreilly.com/2010/03/what-is-a-packrat-parser-what.html. Retrieved 23 Nov 2010.

- ^ for example, the LISP expression (x (x (x (x ....))))

- ^ a b Alessandro Warth, James R. Douglass, Todd Millstein (January 2008) (PDF). Packrat Parsers Can Support Left Recursion. Viewpoints Research Institute. http://www.vpri.org/pdf/tr2007002_packrat.pdf. Retrieved 2008-10-02.

- ^ Ruedi Steinmann (March 2009) (PDF). Handling Left Recursion in Packrat Parsers. http://n.ethz.ch/~ruediste/packrat.pdf.

- ^ "Packrat Parsers Can Support Left Recursion". PEPM '08. January 2008. http://www.vpri.org/pdf/tr2007002_packrat.pdf. Retrieved 2009-08-04.

- ^ Bryan Ford (2002) (PDF). Functional Pearl: Packrat Parsing: Simple, Powerful, Lazy, Linear Time. http://pdos.csail.mit.edu/~baford/packrat/icfp02/packrat-icfp02.pdf.

- Medeiros, Sérgio; Ierusalimschy, Roberto (2008). "A parsing machine for PEGs". Proc. of the 2008 symposium on Dynamic languages. ACM. pp. article #2. doi:10.1145/1408681.1408683. ISBN 978-1-60558-270-2.

External links

- Parsing Expression Grammars: A Recognition-Based Syntactic Foundation (PDF slides)

- The Packrat Parsing and Parsing Expression Grammars Page

- Packrat Parsing: a Practical Linear-Time Algorithm with Backtracking

- The constructed language Lojban has a fairly large PEG grammar allowing unambiguous parsing of Lojban text.

- The Aurochs parser generator has an on-line parsing demo that displays the parse tree for any given grammar and input

- REBOL parse dialect is PEG-compatible

- Parboiled is a mixed Java/Scala library for building PEG-based parsers

- Mouse transcribes PEG into a set of recursive Java procedures